Books and Writing

Books and Writing

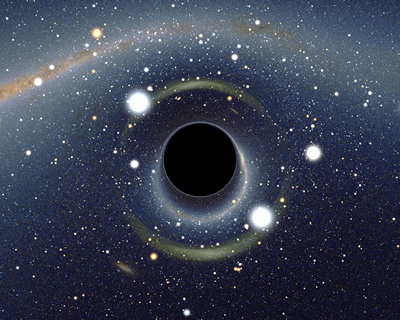

Writing into an Abyss

- Details

- Published: 20 February 2014 20 February 2014

Each time I write, it’s always the same. I start on a blank page with a subject in mind and proceed, sometimes not knowing where I’m going or whether I’m equipped to make the journey, but going anyway.

Each time I write, it’s always the same. I start on a blank page with a subject in mind and proceed, sometimes not knowing where I’m going or whether I’m equipped to make the journey, but going anyway.

It’s on this journey that I find my way, the journey of a thousand miles beginning with the first step, those first thoughts that become the stepping stones to the next leg of the journey.

I like to use the metaphor of ‘journey’ to refer to the writing process, for writing, like life, resembles a ‘journey’, where there is an element of uncertainty, adventure and difficulty. There are all kinds of gradations that force you to move at different speeds, depending on which plane you are traveling – up, down or on flat surfaces. Sometimes you find yourself accelerating; other times, stuck in the mud. It can be a real roller coaster ride or like driving a bumper car in circles, going front and back, bumpety bump, returning you to just about where you started.

When you begin writing, in whatever mode or method you start out, you make your way forward, down the page, word over word, paragraph by paragraph, in no exact order, to realize that you have advanced because you have kept at it, if for no other reason, than persistence.

Persistence is a thread that keeps things going, but it is not the glue that adheres the whole. That’s where vision comes in, where purpose helps drive the ship, even if you are writing into an abyss.

You might say that there is an inner logic only you can understand when you are writing. How that logic appears on the outside depends on how attuned you are to your audience, where they’ve been and the truth that resonates between you and them.

As a writer, all I really care about is now because if I start to focus on the end, whether it’s the end of a sentence or the end of a story, it is like projecting into the future, which is hard to predict, especially if there is no precedent or pattern to which you can look. Take away the surprise, the mystery of the future, and why bother?

As your journey is underway, time somehow forgives you for moving in all directions, which is a given for this writing life and its elastic nature and how it bends to fit the new landscapes that you create going between the past and the future while trying to stay present. Time is always a factor, a constraint to some extent, but a necessary element that is part of moving forward.

I repeat. You must go back to move forward. And vice versa.

When you realize that you only have so much time, whether it is time to get published or time to wrap it up or time to put it away or time to make a living or the many other myriad uses of time, time has the final say, stepping in to bring things to an end.

It is a weird feeling to be writing into an abyss, with no agenda per se, except to advance and hope for the best.

Where are you going? Why are you going there? What is it that you have to illustrate? What is it that you must communicate?

In this darkness you discover why you have come. It is simply another exercise in which practice makes perfect. Although an exercise of sound and fury signifying nothing, thru the abyss there is light and, you, a timeless traveler, passing through.

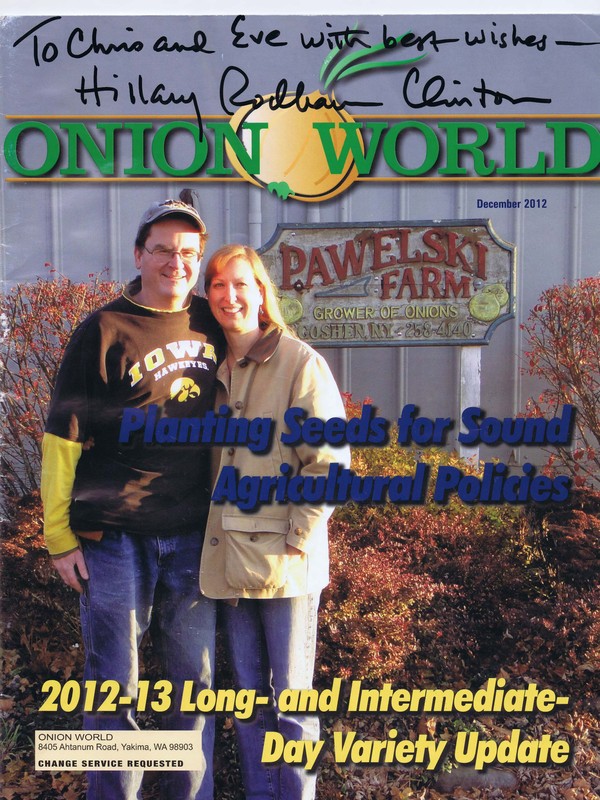

Muckville: A Memoir of the Public Policy Life of a Farmer

- Details

- Published: 07 December 2013 07 December 2013

PROLOGUE

Muckville. I can see you asking yourself now

Why should I care about a book about farming? Or one about public policy advocacy and dealing with the media? Or a book that combines the realities of farming with agriculture-specific policy, advocacy and dealing with the media?

We all have to eat. Every day if possible. Day after day. Until we die we have to eat. Food, along with breathable air, clean water and adequate shelter is one of our most basic needs. Since there are roughly 3.3 million farmers in the U.S. comprising roughly 2% of the general population, odds are you have never met a farmer. Despite the growth in popularity of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) and local farmers’ markets it is most likely you have never met, spoken, smelled or touched a farmer. Or set foot on a farm.

Though the United States was once primarily an agricultural society and even as recently as the turn of the previous century roughly 40% of the population farmed, since then, and especially since the advancements associated with Norman Borlaug’s “Green Revolution” fewer and fewer farmers on less and less land space have produced one of the world’s safest, most abundant and cheap food supplies.

With that change has come an incredible level of disconnect between the people who primarily produce our food and the citizens who eat it. Sadly, when you mention the word farmer the first image that will pop into someone’s head will be Eddie Albert’s character Oliver Wendell Douglas from the CBS sitcom “Green Acres.” Or worse, some character from one of the various reality TV shows that keep popping up, and frequently aren’t so real.

Though farmers’ markets are exploding across the country and thanks to the foodie movement there is a strong renewed interest in agriculture, much of the information about farmers is not coming from us. Food critics and chefs will frequently pontificate about farming, and though some of them may have a small hobby farm, for the most part they are not farmers. They do not know what it is like, on a day to day basis, to be a farmer in the 21st century.

I simply don’t have enough heads for all the hats I have to wear. I have to be a soil scientist, a chemist, a financial planner, an accountant, a bookkeeper, a regulator, a marketer and frequently a public relations person and public policy advocate.

Farming today is governed by a myriad of laws and regulations that cover numerous aspects of our business on multiple levels. And there are so many groups, organizations and pressures out there trying to influence or change those laws and regulations on a seemingly daily basis.

In the mid 1990’s after leaving the farm a short time to pursue my graduate degree and after I married my wonderful wife Eve, I returned to the family onion farm. My brother and I are the fourth generation of the same family on a farm that started in the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century. As soon as I returned I started dealing with a variety of issues and crises, including weather disasters and various labor advocacy organizations. I was baptized by fire. Eve and I had to learn, for the most part on our own, how to fight for our farm and our industry. It wasn’t easy at first (for the most part it still isn’t now, 17 years later). But, trial by fire typically isn’t.

So why is this all important to you? Because as I said, we all have to eat. It’s one of our most fundamental needs. You should know something about how your food is produced. Not from sitcoms, or from food critics or from chefs, no matter how well intentioned they may be. You should know from one of us who produces it.

Now, there are some books out there written by farmers about farming. Many of those books are about the adventures of people who eschew urban or suburban life to move to the country and take up farming. They extol the benefits of a more simple life.

That’s not the point of this book.

Life is not simple, nor, quite frequently, very fair. A hailstorm that decimates your crop mid season or a hurricane caused flood that wipes virtually your entire crop away is not fair. And how you deal with those scenarios is anything but simple. I’ve dealt with those situations, sadly, more than once. I’ve also dealt with very stupid government programs and terrible proposed legislation. And over the years my wife and I have had a fair number of successes in dealing with such situations. That’s what this book details.

Though it is a memoir about my specific experiences on the farm and in front of a camera or on Capitol Hill, what I relate, the techniques and the tricks and methods of dealing with the media or developing grassroot strategies to fight for a given issue can be applied by you. No matter what you do, or where you live, or what problem you may be facing, my example can provide you with a roadmap to how you can successfully fight for your cause.

The system is messed up. It sucks, to be quite frank. But my specific experiences show that if you are persistent and you have a fraction of a clue as to what to do, you can make a positive change for your community, too.

Why should you read this book? Because I need better informed end users of my product. I need you to understand why after a devastating hailstorm or flood, I need your support and help. I need you to have a better connection with the people who produce the food you eat. And, you need to better understand the people who grow your food, and how the policy decisions can affect every aspect of the food you eat.

Why should you read this book? Just as important as learning about how your food is grown, I want you to read it and to realize that you can get off the couch and fight for your family and your community. Though the deck is stacked against you, like it is against me, you can still effect a positive change. All is not bleak. There is hope.

I want you to read this book so that the next time you walk into the produce section of your local supermarket you will pause for a moment and just think about what was involved to get those fresh vegetables and fruits on that shelf.

A NOTE FROM EVE

A NOTE FROM EVE

Muckville. That’s where we live, both literally and figuratively.

And every day something weird is happening on this farm. In the early years I kept waiting for it to end, waiting for calm. After 20 years I now realize that for better or worse, that’s just not going to happen. Part of it has to do with who I married. I think he described it best one night when we were talking about how people react to adversity. He said, “People basically fall into one of two categories: sheep or wolf. And I’m not a sheep.” I think I am a sheep who hitched a ride with a wolf. When we lost our crop to hail the first time in 1996 and our insurance turned out to be worthless and I was pregnant and large amounts of debt loomed on the horizon, I was perfectly willing to throw up my hands, quit and go do something else. In that respect I think I am like most people. Life is just easier if you can go along with the flow and avoid the pitfalls. But if everyone did that improvements would seldom if ever be made.

If I’ve surmised anything over the years, it’s that problems come about seemingly on their own resulting from a convergence of factors: a misinterpretation of a law or regulation, a quirky personality, a do-gooder who is just plain wrong, and/or a bureaucrat who refuses to do anything other than “the way it’s always been done.” The result is that change takes a lot of work but more importantly perseverance.

So what do you need to make a change? The first quality just about everyone has. It equates to “What the @#$% happened here?” The second quality many people have, “I’m mad. I’m going to complain to the proper authorities, and this will be fixed!” But there are a lot of problems out there and it is just as likely that your problem won’t be fixed. Sure some may complain for a while but at some point most people simply cut their losses and walk away grumbling. If you are really determined to make a change, it takes more than complaining. Change comes about because you can articulate exactly what is wrong and why, AND you have mapped out and researched what should be done instead. Only then do you have a chance.

Chris (God bless him) has chronicled several things we have fought to change. Some of it is humorous. a lot of it comes under “You just can’t make that up!” and parts of it I simply cannot read because it was enough for me to live through it. We hope that you will be entertained and learn a little about production agriculture along the way. But what we really hope is that maybe the next time you see a problem, you will have the courage to be a wolf.

Chris is seeking public support to help fund his project. To find out how you can help support him, go to website https://fundrazr.com/campaigns/1efvb/ab/61mkb2